Bechukosai: And Still, We Walk Tall

On the brink of entering Eretz Yisrael, after Hashem gave us most of His mitzvot, we entered into a sacred covenant with Hashem. This solemn bris, presented in Parashat Bechukosai and reiterated in Ki Tavo, binds our national destiny to our moral and religious choices. If we follow the ways of Hashem, we will dwell in the land with peace and berachah. But if we stray, we will face hardships and ultimately, galus.

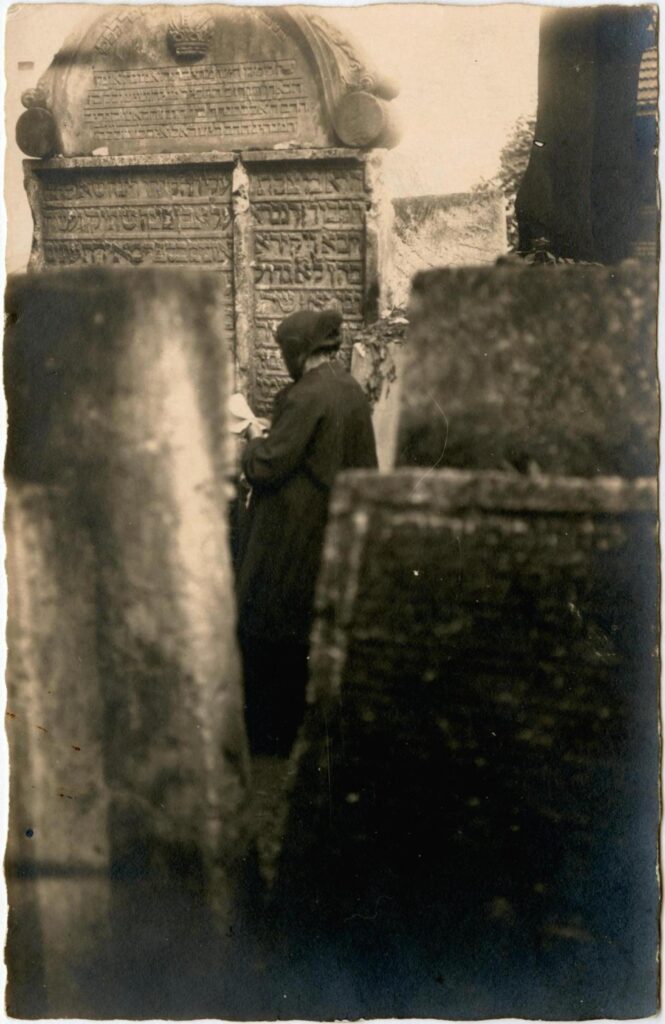

This brit, etched into our history as the tochachah, the great rebuke, has heartbreakingly been fulfilled. Twice we were torn from our homeland, cast into galus under the weight of our own spiritual failings.

Most of the berachot we were promised lie beyond our control. We cannot summon rain, nor can we guarantee the ripening of crops. Despite our efforts, we cannot dictate the behavior of our neighbors or ensure they remain peaceful.

Yet among the many promised berachot, there is one that lies, at least in part, within our hands. Hashem promises to liberate us from an oppressive yoke, v’eshbor motot olaychem (I broke the pegs of your yoke), allowing us to walk tall and proud. The Torah describes this elevated state with the word komemiyus—walking upright, not only in posture but in spirit. Although Hashem shapes the circumstances that can elevate or diminish our national pride, we are not completely passive. We choose how to view our people and our story. History may confront us with sorrow and struggle, but we still choose whether to respond with pride and confidence—or with frustration and self-doubt.

Ideally, religious people feel proud of their Jewish identity regardless of historical circumstances. We alone were chosen by Hashem to live a life aligned with His will and to bring light to a world that is often dark and disoriented. The privilege of living in Hashem’s presence, studying Torah, and following His will should radiate an inner pride, untouched by the chaos that swirls around us. History may rise and fall, but the pride born of religious experience is eternal—beyond the grasp of history’s harsh hand.

However, history also affects our inner pride, and the past eighty-five years have unleashed a storm of challenges to our pride as Jews.

After two millennia of galus and discrimination, Jewish pride hit its lowest point in the wake of the horrors of the Holocaust. Our people were broken and scattered, left to wonder how Hashem could allow such darkness to unfold. To echo Abba Kovner, a partisan who survived: “We are the remnants of a people…shadows of the murdered.” In those shadows, it was hard to find room for pride in the historical destiny of the Jewish people.

Nineteen forty-eight was meant to change all that. The birth of the State of Israel was widely considered an opportunity to restore dignity to our people. The War of Independence was called the war of komemiyus (uprightness) in the hope that it would revive our shattered pride.

Without question, the establishment of the State of Israel was a monumental event, answering the Holocaust both spiritually and practically. This miracle is forever etched in modern Jewish history. Yet Jewish pride was still searching for its footing. Our new state was only a glimpse of the homeland we had dreamed of. We were a young and fragile nation—struggling financially, surrounded by hostility, and still finding our place in the broader family of nations. Many Jews emigrated to Israel fleeing persecution in Arab lands. Many others emigrated from Israel looking westward for stability and opportunity. The year 1948 brought hope and relief, but the komemiyus we had yearned for had not yet fully arrived.

1967

That moment arrived in 1967, with our return to the heartland of Jewish history, and of course, to the sacred city of Yerushalayim. Coupled with the breathtaking nissim and military victories of the Six-Day War, which we celebrate this coming week, Jewish national pride was electrified. Waves of pride surged throughout the country.

This pride was not confined to the hills of Yerushalayim or the shores of Tel Aviv. It rippled eastward to Jews living in the Soviet Union, whose Jewish identity had long been suppressed. Their renewed pride, sparked by the Six-Day War, ignited a movement that ultimately brought millions of Jews home to Israel.

The ripples of Jewish pride also spread westward, igniting a revival of Jewish spirit in Western countries. For many religious Jews, this renewed pride in the wake of 1967 sparked a religious revolution: greater observance and renewed shmirat hamitzvot. Even among non-observant Jews, it brought a newfound confidence in embracing and celebrating their Jewish identity. The komemiyus that eluded us in 1948 finally awakened in 1967.

In the fifty-eight years since 1967, life in Israel has become increasingly entangled in political and social complexities. Over time, pride has worn thin for many Israelis. Abroad as well, Jewish pride didn’t break or vanish—it slowly dissolved as many quietly blended into surrounding cultures and identities. The vibrant pride that surged in 1967 still echoes, but for many, it has slipped from immediate feeling.

October 7th changed the equation. Confronted by unspeakable violence and inconceivable hatred, many Jews around the world have chosen to stand tall against cruelty and moral collapse, embracing a deep belief that we stand for something better, something nobler, for ourselves and for all humanity.

In many ways, October 7th echoes 1967—a moment when Jewish pride was renewed and Jewish identity surged with fresh intensity. We fervently pray that Hashem helps us reclaim our national pride through victory and success and not, chas v’shalom, through future hardship or suffering.

Pride is a quiet form of national currency, often determining whether cultures flourish or falter. Part of the unease gripping the West today lies in its growing struggle to take pride in its own story. We’ve shifted from a generation once celebrated for courage and conviction to one that often feels uneasy about its cultural roots. Unsure how to honor the world they’ve inherited, many turn inward, questioning their own institutions and values, viewing the West as stained by perceived ills of the past.

Maybe this helps explain the deep hostility toward us. Jews don’t hide our national pride—we speak openly about our story and believe in the justice of our cause. For many in the West, that confidence can feel jarring. It may hold up a mirror they would rather not face. And so, they turn outward—projecting onto us all the wrongs they associate with their own history.

Pride is not merely a state of mind or an emotional feeling, it is a conscious choice. When we face adversity and challenge, both from within and from external enemies, we confront a decision: Do we stand tall and embrace pride in what we have accomplished or do we fall into worry, panic, and self-doubt? Do we let internal divisions convince us that we are broken, and do we continue to feed the narrative of a fractured society?

In this crucial battle, every person, whether they serve in the army or not, whether they live in Israel or not, is part of the struggle. Walking tall is a responsibility for all of us, not just to overcome those who seek to break us, but to strengthen our own resilience and national vitality.

As we mark the anniversary of 1967, remember your place in history. Pride came more easily then. In 2025, the challenge is more complex, more nuanced. We can choose to sink or to rise. We can bend or we can stand tall. That choice is ours—and it will shape our future as a nation. n

Rabbi Moshe Taragin is a rabbi at the hesder pre-military Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, was ordained by YU and has an MA in English literature from CUNY. His most recent books include “Reclaiming Redemption: Deciphering the Maze of Jewish History” (Mosaica Press) and “To be Holy but Human: Reflections on my Rebbe HaRav Yehuda Amital” (Kodesh) are available in bookstores and at MTaraginBooks.com.