A Journey to 16th Century Venice: Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz of the House of Baruch and his Remarkable Impact on the Talmudic Daf

Whether you call it the Daf, a blatt of Gemara, or the Talmudic folio, the ancient pages of the TalmudBavli are the cornerstone of Jewish life. With the establishment of the Daf ha-Yomi by Rabbi Meir Shapiro in 1923, the daily study of the Daf has seen unprecedented growth in the past hundred years. With the technological advancements of the 21st century, global Daf networks have been established and are growing at remarkable rates, beyond the imagination of the movement’s founder. Although the Daf Yomi is so much a part of our daily lives, it’s worth noting that in the broader picture of Jewish history, the Daf Yomi is a relatively new invention.

Did Rashi and the Rambam study Gemara from the same Talmuds we use today? What did the study of the Talmud look like in the prominent Talmudic academies of the Ramban and the Rashba?

In this article, we will journey to northern Italy to encounter the creators of the Daf Gemara.

Life Before The Daf: The Era of Talmudic Manuscripts (Kisvei Yad)

From the time the Talmud was written (around 500 C.E.) until the invention of the printing press in Europe in the 1460s, those who studied Gemara from a written text did so from hand-written manuscripts. There is some evidence, however, that at least during the Geonic period (approximately 500-1000 C.E.), Gemara was largely studied Ba’al peh (by heart), despite the fact that written texts existed (see Meiri in his introduction to Avos).

As one might imagine, the production of hand-written Talmudic manuscripts was both time consuming and expensive. As such, during the Medieval period, Talmudic manuscripts were not widely available to the general public.

Thus, the philanthropy of the 11th century Spanish Rishon, Rabbi Shmuel ha-Nagid (also known as Samuel ibn Naghrillah) bears mentioning. This wealthy vizier of the Muslim king of Granada generously sponsored the production of Talmudic manuscripts (and Geonic writings) to scholars in need. At a time when Talmudic manuscripts were simply not affordable to the average Jew, Rabbi Shmuel ha-Nagid’s noble deeds greatly enhanced Talmudic scholarship in many countries beyond his native Spain.

We can also better understand the devastating effect of the “Burning of the Talmud” during which more than 1,000 Talmudic and rabbinic manuscripts were incinerated in Paris in 1242. Since Talmudic manuscripts weren’t mass produced during the Medieval period there was no centralized entity charged with their publication. Without any formality in production there was no tzuras hadaf, or standardized page layout. Rather, each individual would have his Talmudic manuscripts written in the size he preferred and with the commentaries he desired.

The Advent of Printing and the Development of the Daf

The tzuras hadaf with which we are familiar began to take shape at the turn of the 16th century as the printing press gained momentum (primarily in Italy) and Jewish and non-Jewish printers began printing the Talmud Bavli.

The Soncino Edition of the Talmud Bavli

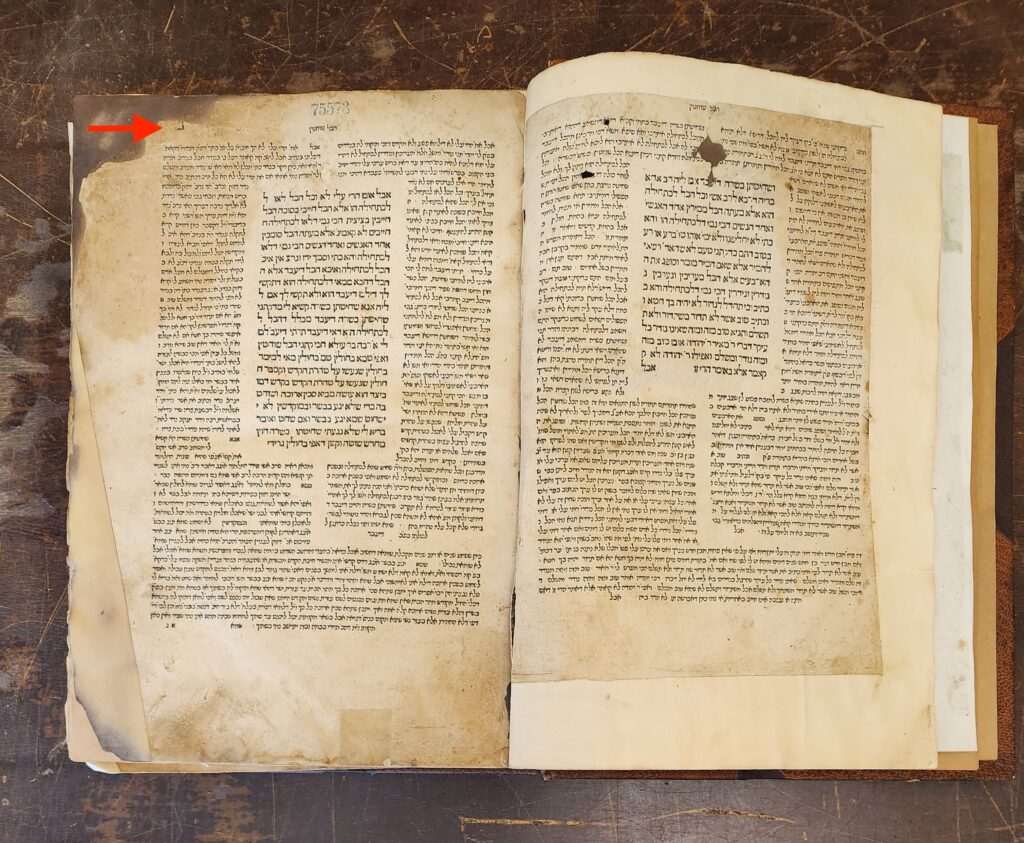

Aside for perhaps some slightly earlier printings in the Iberian Peninsula, the first printing of the TalmudBavli was by the Soncino family in 1489. As you can see from the picture, the margins are completely empty with the exception of a page number that appears in the top left corner. However, the page number was not actually part of the printing, but was added later, presumably by one of the owners.

Rashi and Tosafos appear on the two sides of the Talmudic text, thus giving the page the general tzuras hadaf with which we are familiar. Aside from Rashi and Tosafos, the Soncino edition did not contain any additional commentaries.

The Bomberg Edition of the Talmud Bavli

The Daf changed dramatically when Daniel Bomberg printed his various editions of the Talmud Bavlibetween 1519-1549. Bomberg and his staff were the first to introduce pagination, in other words the concept of the Daf!

They also selected several additional commentaries to be printed at the end of the volume: Piskei Tosafos, Rambam’s Perush Mishnayos (although for some reason the Rambam’s name is omitted), and Piskei ha-Rosh.

The Giustiniani Edition of the Talmud Bavli

Daniel Bomberg’s innovation of the Daf paved the way for his apprentice, Marco Antonia Giustiniani, to significantly enhance the study of the Talmud Bavli. In 1545, Giustiniani hired a Spanish refugee named Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz (author of Shiltei ha-Gibborim on the Rif’s Sefer Halachos) to add important reference tools to the Daf.

These three works, which were printed on the margins of the page, are indispensable to the student of the Talmud:

1. Torah Ohr references the perek (and sometimes pasuk) in Tanach which the Gemara quotes. This enables the student to quickly locate the full pasuk, understand the context, and look up other relevant commentaries. In newer editions, Torah Ohr has been upgraded to include a citation of the entire pasuk that is being referenced.

2. Mesores ha-Shas cross-references other Talmudic sources mentioned in the Gemara, Rashi, and Tosafos. In the 18th century, Rabbi Yeshayah Pik Berlin (1719-1799) expanded and upgraded the Mesores ha-Shas. The value of this work is immeasurable when considering the fact that many Talmudic sugyos (subjects) are scattered throughout the vast “Sea of the Talmud.” With relative ease, we can flip through a two- or three-hundred-page masechta and find the precise words within minutes.

3. Ein Mishpat references the halachic works relevant to a specific passage of the Talmud. In its original form, Ein Mishpat referenced the primary halachic codices of its day: Rambam’s Mishneh Torah, Semag, andTur. This work is exceedingly important for one who is seeking to understand how the codifiers (such as the Rambam, Tur, and Shulchan Aruch) understood the halachic conclusions of the Talmud. n

Nosson Wiggins (@jewishhistorysheimhagedolim) is the author of two books on the subject of Jewish history, “The Tannaim & Amoraim” and “The Rishonim” (Judaica Press). He researches Jewish History at the Klau Library, HUC-JIR in his hometown of Cincinnati and leads tours of Klau’s Rare Book Room. He is a passionate enthusiast of Jewish history and when he’s not in the hospital working as a nurse, he can be found researching and writing posts for his Substack, “Jewish History—Sheim Hagedolim.”