Exploring Jewish Heritage In Poland And Lithuania With Touro University

By Henry Abramson

Returning to my ancestral Lithuanian shtetl after nearly a century, I had some idea of what to expect. I knew that the synagogue had been turned into a gymnasium, and I knew that a striking monument stood sentinel over the mass grave of my ancestors. I was unprepared, however, for the message sent by the Global Positioning Satellite signal.

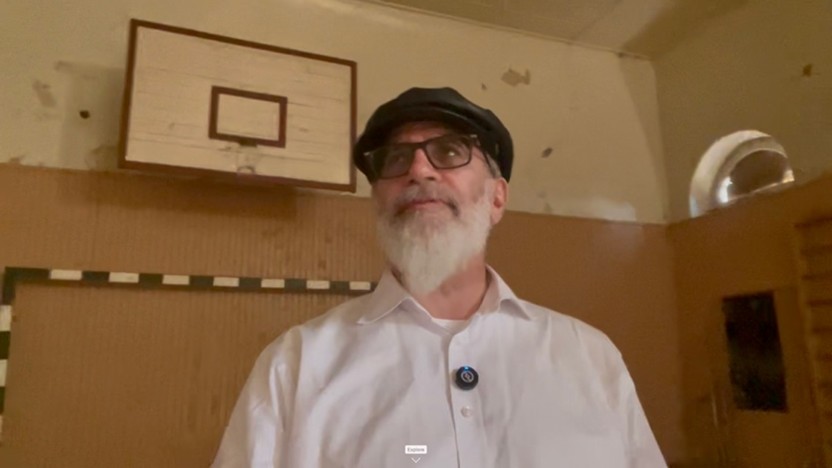

The author inside the synagogue, the Eastern Wall behind him

Many are familiar with the great 18th century Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman, known as the Gaon of Vilna. Today, the modern-day Gaon of the city of Vilna is Dr. Shnayer Leiman, with whom I was privileged to lead a journey of discovery of Jewish heritage in Poland and Lithuania this summer. Our itinerary focused on two major cities, Warsaw and Vilnius, with day trips to surrounding sites where we celebrated the 800-year history of Jews in the region and commemorated their sudden and near-total destruction in the Holocaust.

Dr. Shnayer Leiman at the grave of the Vilna Gaon

Warsaw, the second-largest Jewish center after New York City before the war, features the beautiful, award-winning POLIN Museum, with its near life-size reproduction of the painted ceilings and bimah of the 17th-century Gwózdziec synagogue, an impressive example of a lost Jewish folk art. Our tours took us to the remnants of the infamous Ghetto walls, the Umschagplatz where the Nazis deported some 6,000 Jews a day to their deaths, and the archaeological digs currently uncovering the underground bunkers of the Jewish resistance at Mila 18. We made the trek to the site of the death camp Treblinka and rendered memorial to the hundreds of thousands of Jews who died there with a moving Kel Malei Rahamim recited by Rabbi Moshe Krupka, Executive Vice President of Touro University.

Reproduction of the glorious Gwozdiec Synagogue interior

We marked our time in Warsaw with a study of selections from the Holocaust sermons of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira, the Aish Kodesh (visited the site of his Beis Medrash in the Ghetto), and remarked on his message that we Jews are forbidden to stand paralyzed by the overwhelming tremendum of the Holocaust. In this context we had the welcome opportunity to visit and even daven in two synagogues that survived: the 17th century Tiktin (Tykocin) synagogue and the Nożyk synagogue just steps away from our hotel in Warsaw. We even had the privilege of celebrating a siyum of tractate Menachos in the famed Chachmei Lublin, the Yeshiva founded by Rabbi Meir Shapiro, the creator of Daf Yomi. Chachmei Lublin was revolutionary for its age—breaking with the traditional system of farming students out to local families for daily meals, a practice that Rabbi Shapiro felt was demeaning to budding Torah scholars, the Yeshiva was the first to feature an in-house cafeteria, where Touro University proudly hosted the seudat mitzvah following the siyum.

Our tour also celebrated the life and work of many colossally important rabbis, with visits to their last resting places: Dr. Leiman regaled us with tales of their scholarship, piety, and even humor as we stood by the graves of the Vilna Gaon, Rabbi Elchonon Spector, the Maharshal, Reb Chaim of Brisk, the Netziv, and many others.

After a short flight north, we continued our tour from our base in Vilnius (Vilna). We took advantage of the long summer Shabbos by embarking on a walking tour that took us through the old city of Vilna, home to the Gaon himself, out to the home of the famed Chazon Ish, and a late afternoon farbreng at the active Chabad of the city. Sunday’s day trip to Kaunas (Kovno) featured a visit to the Beis Midrash of Rabbi Yisrael Salanter, founder of the Mussar movement, and a gathering at the notorious Ninth Fort where Rabbi Elchanan Wasserman is believed to have been murdered, along with thousands of other Jews of the city.

For me personally, however, the highlight of the journey was the side trip I took to Simnas (Simne), my ancestral home. It was a moving experience to walk in the streets where my family once walked, to say a chapter of Tehillim in the synagogue where they worshipped. I stopped at the pre-war Jewish cemetery, just a small empty plot since all the gravestones were stolen and repurposed after the war and reserved my trip to the killing field for the end of the visit. Traveling in the comfort of my guide’s air-conditioned Volvo, I suddenly realized that I was following the same route that they would have walked on that fateful day, September 12, 1941, when four hundred and fourteen women, children, and older men—the younger men had already been taken away to Alytus and killed—walked some six kilometers into the deep forest, where a trench had already been dug to receive their bodies. The GPS signal began to malfunction, indicating the destination on the screen, but without any possible access, as if to say, “you can’t get there from here.” The last hundred meters, in fact, had to be traversed on foot, a silent pilgrimage to the site of horrors.

I left a stone behind, the traditional token of a Jewish visit to a grave. Speaking alone to ancestors I never met, I promised them what I thought they would have wanted to hear: their suffering and martyrdom is remembered, and their memory lives on in those who survived: my children and grandchildren, not only in America and Canada but even in the revived State of Israel. n

Dr. Henry Abramson is Dean of Lander College for Men, Touro University