The Melitzer Rebbe: A Legacy In Song

By Dov Bergman

Not every rebbe led with a voice. But when Rabbi Yitzchak Horowitz sang, people didn’t just listen—they felt something stir.

His path began in 1896, in the Galician town of Melitz. Born into the distinguished rabbinic line of Rabbi Naftali of Ropshitz, Rabbi Yitzchak was a direct descendant of that revered dynasty. His father, Rabbi Yaakov Horowitz, served as the Melitzer Rebbe. From a young age, Rabbi Yitzchak displayed remarkable depth in learning and character, and he later received semichah from the famed Torah giant Rabbi Yechiel Meir Halevi of Ostrovtza. Yet it was his extraordinary musical talent that would leave a lasting mark—especially after his arrival in America in 1923, part of a wave of chassidic leaders who came to the New World during the interwar years.

Reflecting on his journey decades later, the Melitzer Rebbe would link his musical reputation in America to something his father told him when he was just thirteen. “My father once called me over,” he recalled, “and said: ‘I would truly enjoy it if you learned to sing well—so you could become someone who knows how to sing properly.’ He explained that in today’s world, Torah study alone is not enough—people expect more from a person. ‘That’s why I want you to learn beautiful melodies,’ he said. For years, I didn’t understand what he meant… Only after I arrived in America did I begin to grasp the depth of his words—there was something visionary in what he told me.”

In a land where, during the early 20th century, Torah and mitzvos were often met with indifference, it was the heartfelt strains of chassidic song that helped awaken the spiritual core of countless Jewish immigrants.

A Melitzer presence in New York had already been established decades earlier. By the 1880s, immigrants from Melitz had already established a shul—Anshei Melitz, later known simply as the Melitzer Shul—on the Lower East Side. When the Melitzer Rebbe eventually arrived in New York, he settled nearby and was immediately appointed as the shul’s rav. He quickly became beloved by both the working men and chassidimwho filled the shul each day.

What set the Melitzer Rebbe apart, however, was that he wasn’t only revered as a rebbe—he was also admired for his remarkable voice, heartfelt melodies, and deep sensitivity to the power of song. In many ways, he was seen as a chazzan as well as a spiritual leader. Crowds would flock to his shtiebel on special occasions to hear his moving Selichos or the soulful way he led Rosh Chodesh bentching.

The shul would sometimes become so packed that there was no room left inside—but that didn’t stop anyone. People stood outside on the street, joining the service from there.

In many ways, his role mirrored that of the world-renowned chassidic chazzanim who immigrated to America in the years just before World War I—figures such as Zeidel Rovner and Yossele Rosenblatt, who traveled from shul to shul across the country, inspiring congregations with their stirring chazzanus steeped in Old World tradition—the Melitzer Rebbe became known for his extraordinary voice and heartfelt prayer.

He was invited by countless congregations to lead services throughout the year, especially during the High Holidays. His Mussaf on the Yamim Noraim and Hoshanos on Hoshanah Rabbah were particularly moving, delivered with deep emotion and musical precision. These services drew large crowds, and over time, the Melitzer Rebbe earned a reputation as one of the most respected and sought-after ba’alei tefillah in America.

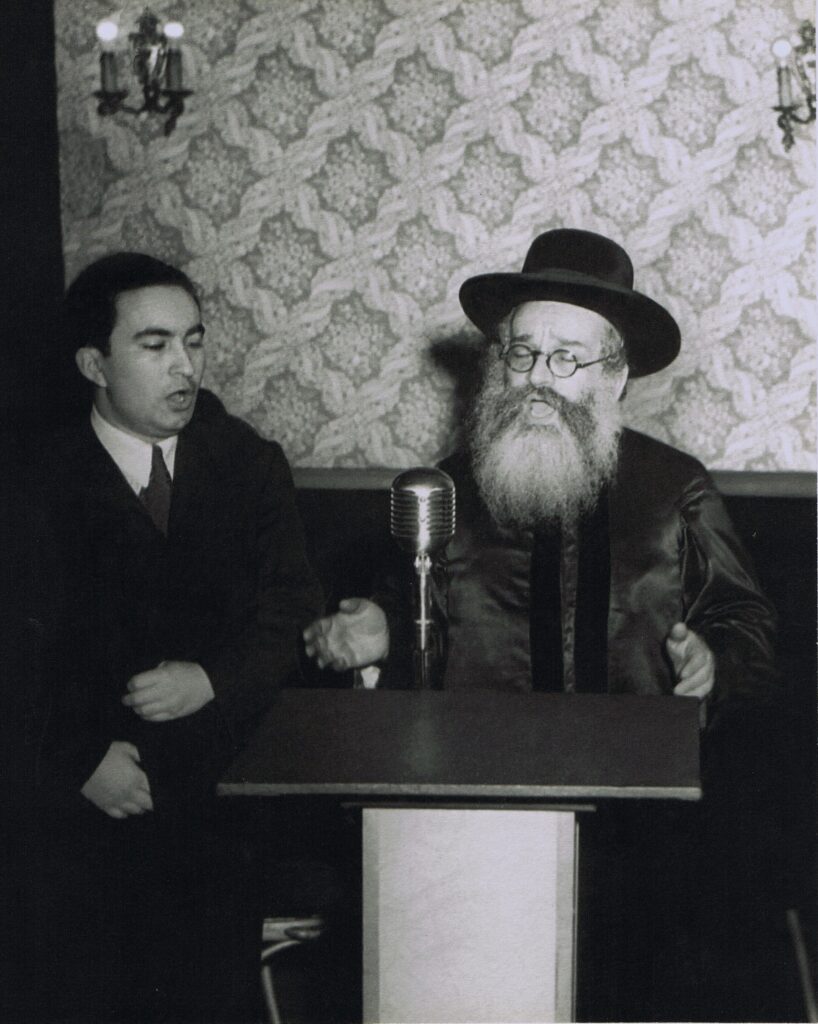

One of the most memorable moments in the Melitzer Rebbe’s life took place during the historic Rabbis’ March on Washington in October 1943, at the height of the Holocaust. Organized by the Vaad Hatzalah and the Agudas Harabbonim, the march brought over 400 Orthodox rabbis to the nation’s capital to urge the Roosevelt administration to take meaningful action to save Europe’s Jews.

At the gathering, the Melitzer Rebbe led the crowd in a moving Kel Malei Rachamim, in memory of the Jews being killed across Nazi-occupied Europe. Then, in a powerful gesture, he sang Hanosen Teshuah L’melachim—the traditional prayer for the government—to the tune of the American national anthem. It was both a sign of respect for the United States and a plea for its leaders to take action. Everyone joined in.

In 1961, the Melitzer Rebbe broke new ground in the world of chassidic expression by embracing modern technology in a way few, if any, rebbes had done before. He released a record featuring ten of his original compositions—fusing chassidus with the emerging medium of recorded music. News of the album’s release quickly spread through Jewish circles. Admirers and music stores alike rushed to get their hands on it, and the record became an instant hit.

A glowing review, titled “The Melitzer’s Songs Reach the World,” praised the album as a long-awaited treasure. “Composed and sung by the Rebbe himself,” the reviewer wrote, “these chassidic melodies had lived in his soul for decades and were beloved for their deep connection to both tefillah and niggun.” The reviewer went on to say that the record “marks the beginning of a new era of chassidic song in Jewish homes and communities,” adding that demand had already begun to grow in both Europe and Israel.

That success caught the attention of another pioneer in American Jewish music. Following the tremendous success of the Melitzer Rebbe’s original record, the renowned chazzan David Werdyger— the late father of famed singer Mordechai Ben David, who had played a major role since the 1950s in popularizing chassidic music through his groundbreaking vinyl recordings—decided to include the Melitzer Rebbe’s compositions in his own repertoire.

While the Melitzer Rebbe had recorded his album in a simple, professional studio setting without musical accompaniment, Werdyger took a different approach. He presented the melodies with full orchestration and musical arrangements, similar to the style of mainstream records at the time, helping the songs reach a much broader audience. Among the pieces he recorded were the Melitzer Rebbe’s Yismechu V’malchuscha andMenucha V’simcha—both of which have since become beloved staples of Jewish music.

After moving to Boro Park in the late 1930s, the Melitzer Rebbe settled on 12th Avenue and 50th Street, where he led a small shul from his home. In 1944, he relocated to Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where he presided over a shtiebel located between West End Avenue and Riverside Drive. This became known as the Melitzer Shtiebel and remained his base for the rest of his life —aside from his final years, when he returned to Boro Park. He passed away there in 1978, at the age of over ninety. Even decades after his passing, the songs he sang still echo—heard in homes, sung in shuls, and remembered by those who heard them.