Where Will You Be For The Holiday Prayers?

By Sivan Rahav Meir

Across Israel, preparations are already underway for the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services. During this season in Israel, shuls overflow and many new prayer gatherings open—in kibbutzim, in city squares, and even in tents along the streets.

This week, Yonatan Levy, a hi-tech professional from Givat Shmuel, sent me the following story:

“For several years now, I have been joining the Yom Kippur prayers at Kibbutz Nir Oz in the Gaza periphery. The kibbutz members are joined by a group of religious Jews from Givat Shmuel and Jerusalem, together with alumni of the Hesder Yeshiva in Elon Moreh.

On erev Yom Kippur, dozens of kibbutz residents would come for Kol Nidrei, and the following day, at the fast’s conclusion, many would gather to hear Amotz, a kibbutz member, blow the shofar. The joy would peak when everyone—religious and secular, old-timers and youth—danced together and sang L’shana Haba’a B’Yerushalayim Habnuyah and Asher Bachar Banu Mikol Ha’amim. Even the children would come, wide-eyed, as the air filled with the sound of the shofar.

Each year, we tried to bring a kohen so that everyone could hear Birkat Kohanim. But on our last Yom Kippur there, in 5784 (2023), we couldn’t find one—until we suddenly remembered Ravid Katz, a local resident who came every year for the Ne’ilah prayer. We asked if he could come that year for Shacharit as well, to lift his hands and bless the congregation. Ravid hesitated at first but eventually agreed.

When he arrived in the morning, we understood his hesitation. It was the first time in his life he had ever been asked to give Birkat Kohanim. He turned to Binyamin, one of the organizers, and asked him to explain the order of the blessing.

The moment was moving beyond words: a simple, kind, humble man, standing there for the very first time, raising his hands to bless the congregation with the ancient words: “May the Lord bless you and protect you. May the Lord make His face shine upon you and be gracious to you. May the Lord turn His face toward you and grant you peace.” That moment is forever engraved in our hearts.

Only a week and a half later, on October 7th, Ravid fought heroically with the kibbutz emergency squad—and fell in battle. His body was taken to Gaza and later returned in a military operation. Ravid worked with at-risk youth, was a devoted father, and so much more could be said about his remarkable character.

When I went to comfort his family, they told me how deeply moved he had been on that Yom Kippur, just days before his murder, to deliver Birkat Kohanim. It was clear to me that this was no ordinary blessing but a final gift he left us all—a message of unity, a moment of holiness before his soul ascended to heaven.

This year, we are once again organizing a joint minyan with members of Kibbutz Nachal Oz, now based in Kiryat Gat. The ties have remained and even strengthened. This Yom Kippur, Birkat Kohanim will be dedicated to the memory of Ravid Katz, our kohen, who blessed us only once in his life.”

A ‘Date’ With G-d

The sign at the entrance to the Old City

Every year around this time in Jerusalem, they put up a sign at the entrance to the Old City advising visitors to avoid arriving by car and instead to use public transportation. This year they put the sign up early because of the huge crowds that have been coming since the first day of Selichot.

Ephraim Oren, a teacher, saw this text and wrote: “There’s depth here. Never come to Selichot as a private individual but as part of the public. This isn’t a private matter, it’s a connection to the entire community.”

He’s right. This is a national event. The photo that the Western Wall spokesman sent me after the first Selichot there looked unbelievable to me. I thought it was last year’s last night of Selichot, which is usually the most crowded, but in fact it was from this year; the plaza filled up like this on the first night, and every night breaks the record of the preceding one.

What brings so many men and women to the Kotel at midnight on a weeknight? This week there was a group of bank employees there, alongside Breslov Hasidim, as well as many teenagers and young adults—people you’d never expect to see together, getting along beautifully.

This week, content creator Eliasaf Ezra wrote about this on Instagram. He is using a “new language,” which is very different from the sectarian, political, and media language we’ve become accustomed to: “The best thing you can do for yourselves right now is to travel to Selichot at the Western Wall. Choose an evening. Wear your nicest clothes. Listen to liturgical poems on the way. Fuel your soul with spirituality. Take a deep breath and fill your lungs with holiness. All the parties in the world, all the restaurants in the world, all the dates in the world, don’t compare to this. No date compares to a date with G-d!”

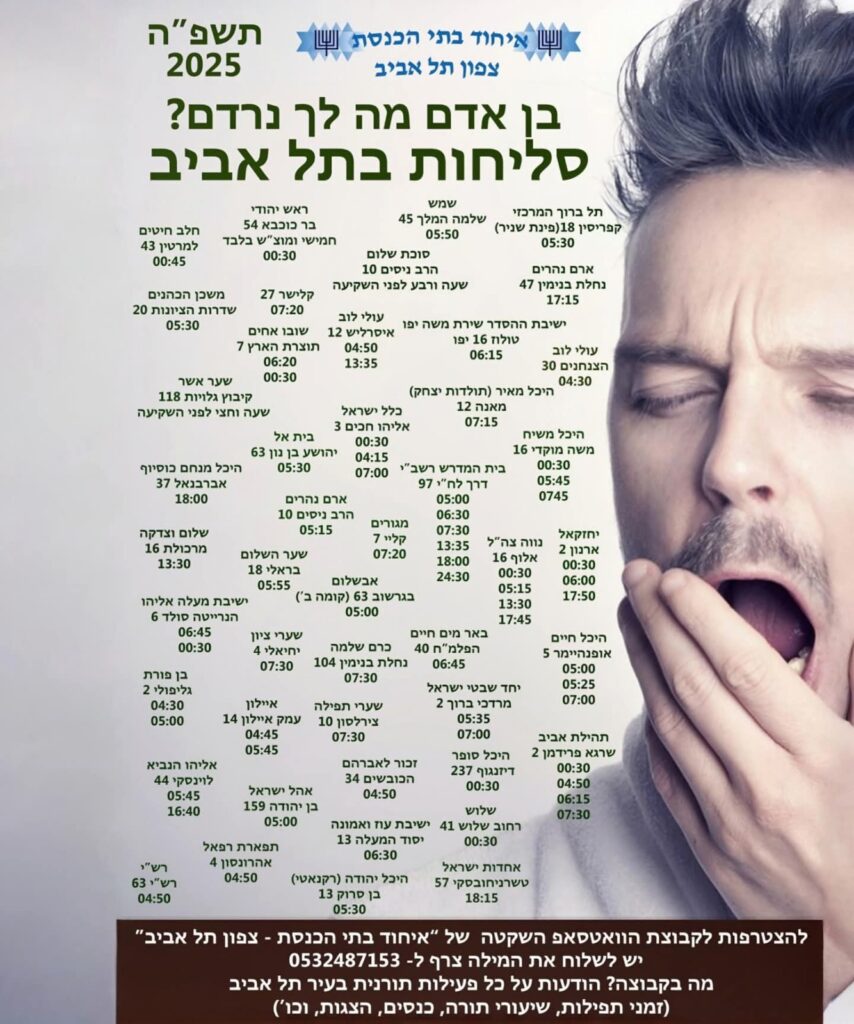

Selichot in the City That Never Stops

An ad for Selichot in Tel Aviv listing some 50 locations

I have been writing a lot about Selichot at the Western Wall—but the story is so much bigger. We tend to see only what photographs well: the crowds, the emotion, the drama. But the phenomenon runs far deeper and wider than that.

Readers have written to tell me: Selichot is not just the Kotel. It’s in a community center in Hadera, in a parking lot in Gedera, on the beach in Eilat, and in synagogues from New York to LA.

And then there’s Tel Aviv—a city often in the headlines for religious-secular tensions. Yet this week, someone asked on a WhatsApp group if there was any place in Tel Aviv to say Selichot that night. In response, she received a beautifully designed flyer listing about fifty locations across the city! And this was not for the first or last night of Selichot, but for an ordinary evening in the middle of Elul. Selichot without pause.

People everywhere are waking up, searching for connection—with Judaism, with G-d, with who we really are. May this awakening continue, and may all our prayers be answered.

The Virtue of Joy

This week’s parashah, Ki Tavo, confronts us with the stark reality of the consequences of our actions. It spells out in painful detail the blessings that can follow obedience, and the curses that can descend when we turn away. The punishments described are devastating: exile, disease, destruction, fear, and the loss of basic security. The description of physical and emotional suffering is almost too much to bear.

And then, in the middle of this long, foreboding list, we come across a verse that stops us in our tracks: “Because you did not serve the Lord your G-d with joy and gladness of heart when you had an abundance of everything.”

Wait—what? Is the Torah really telling us that because we weren’t happy enough, we were exiled, punished, and even destroyed? Could it be that a lack of joy before led to tears and tragedy after?

We often hear that the Temple was destroyed because of sinat chinam, baseless hatred, a communal sin that corrodes society. But here, the Torah points to something deeply personal: that even when life was good, when mitzvot were observed and blessings were plentiful, there was no joy in serving G-d.

Maimonides writes: “The joy a person feels when fulfilling the commandments and loving the G-d who gave them is a great religious achievement.”

Rabbenu Bahya takes it further: “One must rejoice when performing the commandments. This joy is itself a commandment.”

Joy, then, is not a side note. It is the very essence of serving G-d—a mitzvah in its own right. n

Translated by Yehoshua Siskin and Janine Muller Sherr

Read more by Sivan Rahav Meir at SivanRahavMeir.com.